What Do Teachers Really Think About School Discipline Reform?

Not long ago, a student who got into a fight at school would likely face an automatic suspension. Now, in schools across the country, that student might be back in class the next day.

Not long ago, a student who got into a fight at school would likely face an automatic suspension. Now, in schools across the country, that student might be back in class the next day.

Not long ago, a student who got into a fight at school would likely face an automatic suspension. Now, in schools across the country, that student might be back in class the next day.

That change is part of an expansive effort to rethink the way public schools respond to misbehavior. In many schools, punitive measures like suspension and expulsion are being replaced with alternative strategies that aim to keep students in the classroom and address underlying issues like trauma and stress.

Yet, recent polling suggests that those charged with carrying out these reforms — America’s teachers — remain skeptical of policies that could limit the use of exclusionary discipline.

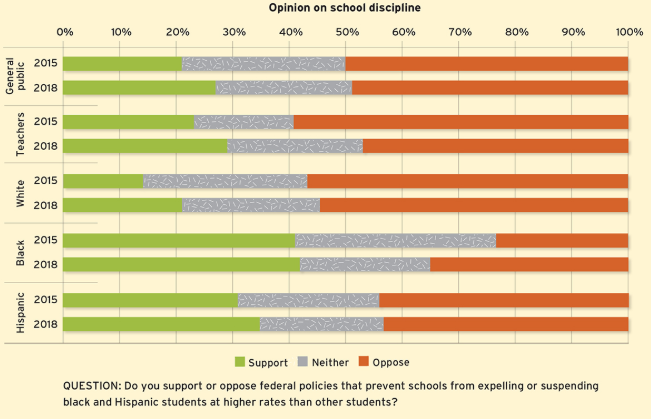

In a recent poll by Education Next, a journal of opinion and research on education policy, just 29 percent of teachers said they support federal policies that prevent schools from expelling or suspending black and Hispanic students at higher rates than other students. Even fewer, 26 percent, support such policies when they come from the school district.

At the same time, according to a nationally-representative survey by Educators for Excellence, an advocacy group, just 39 percent of teachers think out-of-school suspensions are effective at improving student behavior. The same percentage said expulsions are effective in achieving that goal.

The results paint a muddled picture about teachers’ attitudes toward discipline reform. On one hand, most teachers don’t think exclusionary discipline — actions that remove a student from their usual educational setting — is particularly effective. On the other, teachers appear wary of top-down policies that could limit their discretion in disciplining students.

“Whether you think a particular discipline strategy is effective is a distinct issue from whether you think the government should be looking over your shoulder as you make difficult decisions about student discipline in the classroom,” Marty West, a professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the editor-in-chief of Education Next, told me.

The new insights into teachers’ views come as reporting from The Washington Post’s Laura Meckler suggests that U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is likely to rescind school discipline guidance that the Obama administration issued in 2014.

That guidance effectively put school districts on notice — warning that schools found to disproportionately punish certain groups of students could be subject to a federal civil rights investigation. Notably, the guidance stated that even neutral policies “administered in an even-handed manner” could trigger an investigation if they were found to have a “disparate impact” on students of a particular race.

Data from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights show that black students in K-12 public schools are nearly four times as likely to be suspended, and twice as likely to be expelled, as white students. Students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to be suspended as students without disabilities.

Racial disparities in student discipline and efforts to address them are gaining increased attention from journalists. Earlier this year, Erica Green of The New York Times examined how the issues are playing out in the Minneapolis school system.

“The Obama-era policies — and the Trump-era reversals — have divided educators in the Twin Cities,” she writes. “In Minneapolis, as in districts across the nation, discipline policies are more than a political flashpoint. They are a daily struggle to balance safety and statistics, and the uncomfortable truths about how race may be clouding educators’ perception of both.”

‘Teachers Want to Move Away from Suspensions’

Civil rights groups and many on the political left have cautioned against removing the 2014 federal guidance on discipline. In a letter to DeVos earlier this year, civil rights and education groups warned that such a move would send the message that the “department does not care that schools are discriminating against children of color by disproportionately kicking them out of school.”

Among the groups that signed onto the letter were the nation’s two largest teachers’ unions — the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers.

Yet, as the latest polling data suggest, closer to the classroom, teachers’ feelings appear more nuanced.

Evan Stone, the co-CEO of Educators for Excellence, believes that most teachers want to shift to alternatives to suspension and expulsion provided they receive the necessary training and support to make that transition.

“Teachers are tired of districts and states telling them how to do their jobs or manage their classrooms,” Stone told me.

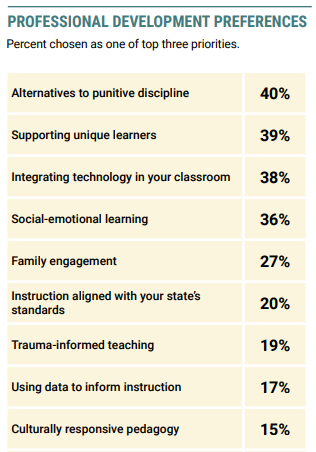

At the same time, “When we ask teachers where they want professional development, the top-ranked thing teachers say they want help with is on non-punitive discipline,” Stone said. “What that tells me is teachers want to move away from suspensions and expulsions, but they don’t want it to be forced on them, and they know they need a lot of help in that transition.”

Educators for Excellence and Education Next each partnered with market research firms to conduct their online surveys, which include representative samples of 1,000 and 641 teachers, respectively.

Confronted with data showing racial disparities in the application of suspensions and expulsions, and under heightened scrutiny from the federal government, states and school districts have taken significant steps in recent years to limit the use of punitive discipline.

In 2016 and 2017 alone, at least 14 states, including California and Texas, enacted legislation directly addressing the use of suspension and expulsion, according to the Education Commission of the States. Arkansas, for example, now prohibits the suspension or expulsion of students in pre-kindergarten through fifth grade unless a student is deemed a danger to themselves or others or “causes a serious disruption that cannot be addressed by other means.”

Many more states have taken steps to encourage, though not require, schools to utilize non-punitive discipline strategies, such as Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS) and restorative justice practices.

While alternative, non-punitive, strategies vary and often look different depending on the school, they generally aim to keep students in the classroom while addressing root causes of misbehavior. Instead of a suspension, for example, students who get into a fight may participate in a counselor-led mediation session where they address underlying issues and brainstorm strategies for avoiding future altercations. Alternative approaches typically emphasize building students’ social and emotional skills.

In addition to reflecting on infractions and their root causes, a key dimension to restorative justice is making amends. The approach is about “building, strengthening, and repairing relationships,” said Troi Bechet, of the Center for Restorative Approaches in New Orleans, during an EWA seminar in February.

“You broke a rule but you also harmed a relationship or relationships in the community and, as a member of that community, you have an obligation in the community to repair that harm,” Bechet said.

The research base for alternative strategies is still relatively limited and studies have shown mixed results on things like student attendance and school safety, as Chalkbeat’s Matt Barnum reported earlier this year.

If the experiences of some states and districts are any indication, amending laws and school discipline policies is the easy part of discipline reform. The greater challenge is providing teachers with sufficient support and resources to change their practices while maintaining safe, orderly, and welcoming classrooms in the process.

In 2015, the Illinois legislature passed a series of measures to reduce the use of exclusionary discipline. But as The Chicago Reporter’s Kalyn Belsha reported this summer, the rollout of those changes has been bumpy.

About half (49 percent) of Illinois’ teachers believe that eliminating zero-tolerance policies has had a negative impact on student behavior and school culture, according to a non-scientific survey released earlier this year by Teach Plus, a national advocacy group that seeks to elevate teacher voices in shaping policy.

A policy brief based on the survey results concluded that teachers have not been provided adequate support and training and that “quite frequently, nothing replaced the disciplinary consequences that were removed.”

“Students weren’t seeing any consequences and just being sent back to class as if nothing ever happened, ” Keira Quintero, a music teacher at a public elementary school in Oak Park, Illinois, told me.

“If you take something away and you don’t replace it with anything else, there’s gonna be problems,” Quintero, a lead author of the Teach Plus brief, said.

As The Hechinger Report’s Emmanuel Felton reported, similar complaints have been issued in other places that have adopted discipline reforms, including New York City.

Despite the challenges of implementation, Quintero said she supports the move to more restorative discipline practices.

“Kids being kicked out of school really sets up the school to prison pipeline,” Quintero said. “Some lawmakers wanted to reverse [the reforms] and we said ‘No, we need this.’”

Your post will be on the website shortly.

We will get back to you shortly