Story Lab: Student Data Privacy

Photo credit: Bigstock/Ja-Images

Published December 2015

Student data privacy is an increasingly high-profile — and controversial — issue that touches schools and families across the country. There are stories to tell in virtually every community. About three dozen states have passed legislation addressing student data privacy in the past two years, and eight different proposals were floating around Congress as of Fall 2015. Corporate titans and ed-tech startups alike have found themselves in hot water over how they handle sensitive student information. And despite in some cases being woefully unprepared, school districts around the country are now under pressure to better safeguard such data through improved policies and contracts.

Nevertheless, you’d be hard-pressed to find another issue on the education beat that inspires more frothy passion based on less information and understanding.

That’s where you come in. This EWA Story Lab will serve as a guide through the big questions to ask, sources to consider, and story ideas you might pursue.

How should reporters begin covering school data safety?

So, how should journalists start in covering such a technical, constantly changing issue? Fortunately for you, districts are facing the same challenge.

A good first step is getting a handle on which third-party vendors are receiving student data from the districts you cover; which data are being shared; and what the approved uses of that information are. Some states now require districts to have publicly accessible inventories covering those questions. If your districts do not, still make it a point to talk about those issues with their chief technology officers (or ask the Consortium for School Networking – the national association of school technology staffers – to connect you with local and state school IT leaders.)

This kind of inventory can be valuable in all kinds of ways. Remember that schools are sharing student data with the developers of classroom tools mostly because they want to improve teaching and learning and make their operations more efficient. Exploring those efforts can lead to great stories, even if there’s not an immediate privacy angle:

- Know what software and apps to look for in the classroom. Maybe the schools on your beat are starting to teach math in a more personalized way, by using programs like Dreambox or Renaissance Learning. Or, perhaps your local schools are trying to reduce headaches for teachers by working with a company like Clever, which helps make it easier to get kids logged into different software programs.

- Start looking at contracts. A widely cited 2014 study led by Fordham University privacy researcher Joel Reidenberg, also the founding academic director of the Center on Law and Information Policy, provides great detail on what should be in the agreements between school districts and these companies, but is often lacking.

- When a company that your district shares student information with lands in the national headlines because of its data-privacy and security practices, you can quickly move to localize the story.

- When your state passes a new student-data-privacy law, or if Congress finally gets around to modernizing the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) – the nation’s 40-year old law on student privacy – you’ll be able to discuss the local impact in tangible terms.

To get a sense of what you might find when you start down this road, check out this great Marketplace piece, “A Day in the Life of a Data-Mined Kid.”

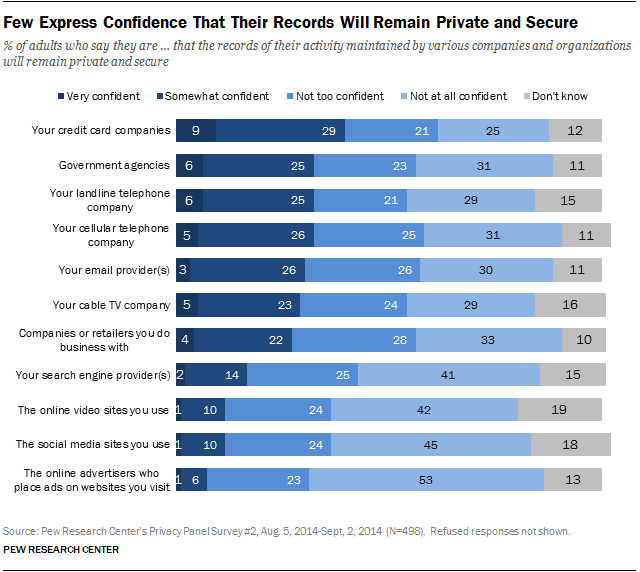

And don’t be surprised if you encounter a large level of distrust among parents that student data can be protected: Adults in the United States place little trust in companies and government agencies to keep personal data safe, a Pew Research Center poll found in 2014.

Source: Pew Research Center (click to expand)

That looks like a lot of companies getting student data!

It really is. Districts in places like Nashville, Tenn., have approved more than 500 different software programs for purchase by schools. And that doesn’t count the dozens of administrative tools they might use, including student information systems, online grade books, and school- or district-wide learning management systems. Nor does it include the classroom apps that individual teachers may decide to try out on their own.

Remember, ed-tech is an $8.9 billion-per-year market, and your districts are paying some of that money. They’re also signing up for “free” tools offered by companies that are happy to take their payment in the form of student information, rather than cash.

When tracking the business side of this equation, what should you be looking for?

Every company will have a privacy policy and/or terms of service document that outlines what they will and won’t do with the student information they collect. The U.S. Department of Education’s Privacy Technical Assistance Center has issued guidance on what those policies should include. Use this as a road map for your own investigations.

- Does the company explicitly prohibit the use of student information for non-educational purposes, including (but not limited to) targeted advertising?

- Will the company share or sell student information to third parties?

- Will the companies use tracking and surveillance technologies that allow them, or third parties, to gather more information from unwitting students?

- What kind of metadata (such as a student’s location, or what type of device they are using) will the company collect?

- Does the company reserve the right to change its policy without notice? (It shouldn’t.)

- What kinds of security protocols does the company commit to using?

These policies can be dense and complicated. There’s also a lot of gray area. Consider tapping experts from places such as Common Sense Media, the Electronic Privacy Information Center, or the Software & Information Industry Association to help you make sense of what you’re seeing and how it fits into the ever-shifting ed-tech landscape. This 2014 Education Week story examining the privacy policies of Edmodo, Khan Academy, and Pearson’s PowerSchool can provide a template.

A short, non-exhaustive list of companies that have come under related scrutiny of one kind or another in recent years includes:

- ClassDojo, a behavior-tracking and classroom-management tool that was called out by The New York Times in 2014 for recording sensitive information about students “without sufficiently considering the ramifications for data privacy and fairness.”

- The above-mentioned Clever revised its privacy policy (which the company said was legal boilerplate, not reflective of its actual practices) after receiving Twitter criticism from ed-tech advocates.

- Google, which admitted to “scanning and indexing” student emails sent using the uber-popular Google Apps for Education. The company says it has since stopped such data-mining for advertising purposes, but questions remain about other potential commercial uses.

- Knewton, which boasts of collecting billions of data points on individual students (and was immortalized in the lede of this Politico story.)

- Microsoft, whose newly released Windows 10 operating system faced criticism in this Education Week piece for sending users’ Web browsing histories and other information back to the company’s servers for storage.

More than 200 companies have now signed the Future of Privacy Forum’s voluntary, industry-led “student privacy pledge” committing to best practices. It’s definitely worth checking out whether the companies used by your districts have signed the pledge. But be aware that it remains unclear whether the pledge will be legally enforceable, or seen as valuable by schools.

The evolving legal landscape

Bookmark the Data Quality Campaign’s legislative tracking site. This organization does an excellent job of keeping up to date on the incredible flurry of student-data-privacy bills and laws in all 50 states.

Some notable trends at the state level to be familiar with:

- Many states’ legislation is focused on regulating the ed-tech industry, often by prohibiting or limiting: the sale of student data, the use of such information for advertising and marketing, and the creation of lasting digital profiles of students. California’s groundbreaking SOPIPA law, passed in 2014, has been a model for many states.

- Some states also have focused on imposing new requirements for state education departments and school districts, including the creation of chief privacy officer positions, development of new data-governance protocols, and establishment of new security and contracting requirements.

- Proponents of effective use of educational data by schools worry that some state laws go too far and will have unintended consequences. One example: A 2014 Florida law prohibited companies from collecting biometric information about students, but some say that law may prevent the use of valuable ed-tech tools, such as language-instruction software that relies on recordings of students’ voices.

Not to be outdone, the feds are also considering a range of measures. Keep an eye on Congress’s efforts to overhaul FERPA.

If and when new legislation is approved in Washington or in your state’s capital, start asking questions such as:

- What existing software programs, apps, and online services already in use by my district might be affected by the new laws?

- What new requirements and administrative burdens will my districts face as the result of new regulations? Who will be responsible for implementing them?

- How will students and parents react?

What about students and parents?

They are huge players in this issue, too.

Just ask the founders of inBloom, a nonprofit educational data repository that was founded in 2011 with $100 million from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. It shut down operations just three years later after being overwhelmed by a vocal group of parent activists who raised privacy concerns from Colorado to Louisiana and New York.

[EWA featured a webinar on the issues surrounding inBloom’s demise.]

Buoyed by that success, the activists have formed a loose group known as the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy. Become familiar with the group, its concerns, and any local parents and activists that are part of the coalition.

Many of the questions concerned parents raise are important to explore in any student-data-privacy story you write:

- Are parents aware of the information about their children that is being shared?

- Do they have the right to opt out from (or into) that process?

- Why is it necessary to share student data with third parties in the first place?

But beware of the biases different stakeholders may bring to the table: Everyone on all sides of this issue has a strong perspective. The ed-tech industry, for example, has a large financial stake in ensuring that any new laws, regulations, and contracts don’t restrict their operations and opportunities to grow. Consider reaching out to GSV Partners, an investment firm that is seen as a leader in financing ed-tech startups and can provide rare insight into what qualities the financial industry looks for in education startups.

Groups such as Common Sense Media, the Data Quality Campaign, and the Future of Privacy Forum are all at heart advocacy groups, with specific agendas they are trying to promote. And some organized parent activists have seized upon student-data-privacy as an issue in part because they see it as a way to combat a larger set of reform efforts that they oppose.