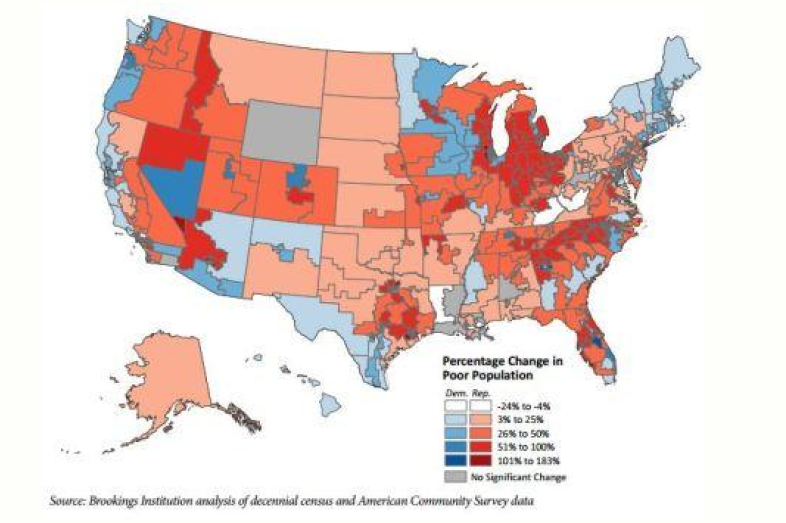

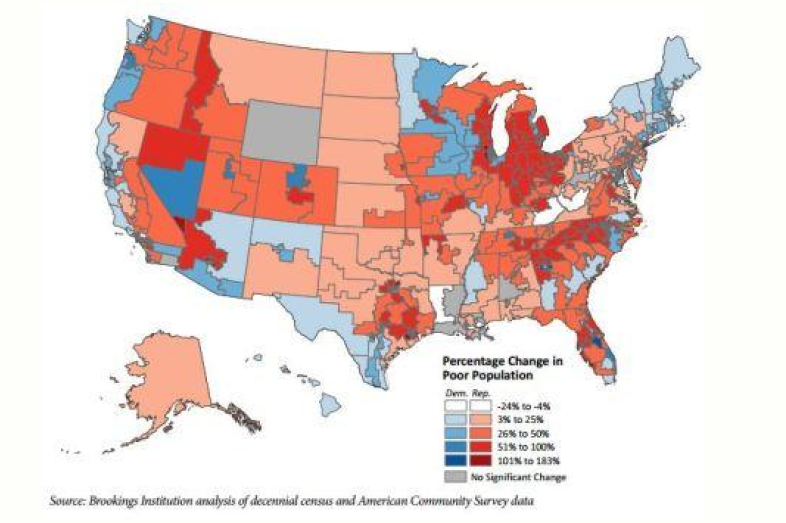

A new report highlighting the growing rate of poverty among suburban residents warns that traditional policies aimed at combating indigence aren’t designed to address the problem adequately. While the findings chiefly focus on the shifting politics of poverty, there’s an education angle as well: Data from the report add to a growing pool of research that suggests schools and universities also are struggling to address the needs of disadvantaged students. How schools adapt to the needs of these students is something that concerns both political parties equally, especially now that Democrats and Republicans represent nearly equal numbers of these low-income neighborhoods.

The report’s authors, scholars at the D.C.-based Brookings Institution, argue that the recent economic downturn has hurt family assets and incomes, driving wealth down and turning traditionally middle-class areas into economically troubled zones. These changes have affected lawmakers from both major political parties equally, the authors note. Nine out of 10 Republican districts saw a jump in suburban poverty between 2000 and 2011; the same is true for eight out of ten districts represented by Democrats.

The new countenance of poverty—three million more Americans who are poor live in suburban areas than in cities—is likely to change at least some attitudes among politicians who previously have given relief programs short shrift. According to the most recent data, 39 percent of students in suburban schools are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch, indicators of low-income status. (Since 2001, the national percentage of students qualifying for lunch programs rose from 38 percent to 48 percent.)

Another potential reason why some politicians might change their perspectives on assistance for low-income families is the economic boost attached to increases in college completion. For every percentage point increase in the number of individuals with a four-year college degree, average local salaries rise by nearly $900 a year, according to a metric devised by CEOs for Cities. Numerous other studies have identified a wage bump as more adults earn college degrees.

But for many low-income students, the odds of completing a college degree are stacked high against them. Academic research has long highlighted the link between socioeconomic status and educational attainment. Students from households in the top quarter of the income ladder are five times more likely to graduate from college than students from the bottom quartile, according to a 2011 working paper. Another study, released last month from Georgetown University, shows that there’s a concrete racial gap in attending selective universities, with whites on one side and blacks and Hispanics on the other side. Far more white students, even with similar high school grades and test scores, enter competitive colleges and universities than blacks and Hispanics, who are over-represented at open-enrollment institutions.

Competitive universities have twice the amount of financial resources to spend on students than open-enrollment institutions. The result is a giant gulf in graduation rates: 82 percent of students successfully complete their studies at competitive schools while 49 percent do the same at open-enrollment schools.

The Georgetown paper’s authors note that many low-income minorities have the high school credentials to attend and graduate from selective universities. They choose not to pursue those options for reasons beyond academics. Experts say some of the reasons minorities don’t enroll in competitive schools are cultural, while others are financial.

Even competitive public universities have a mixed record in enrolling low-income students. At the Universities of California at Berkeley and Los Angeles, a third of the students receive Pell grants. At the University of Michigan, a sixth of students receive Pell grants. And earlier this week the University of Virginia, a school with 13 percent of its students receiving Pell grants, announced it is scaling back a program that virtually covered the cost of tuition for low-income students.

Data and stories that point to the roadblocks low-income students face are legion, and they’re produced almost daily. Perhaps just as frequently, they offer brushstrokes that seen as a whole paint a complex image of how early things start to fall apart.