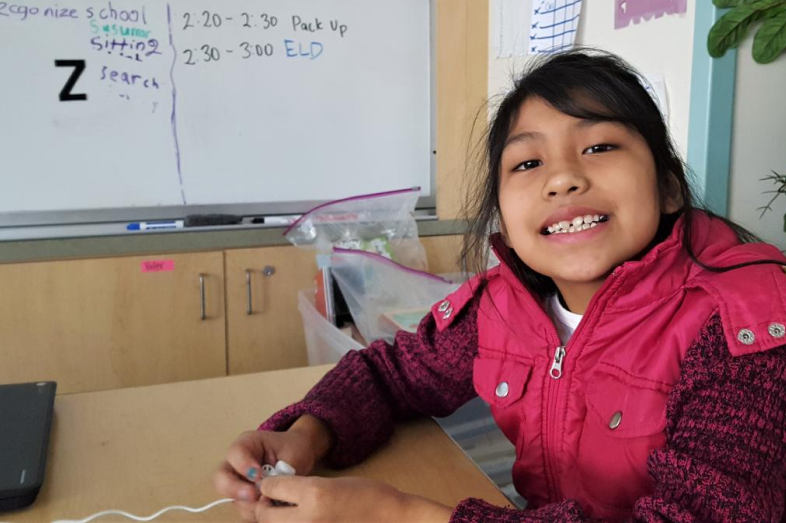

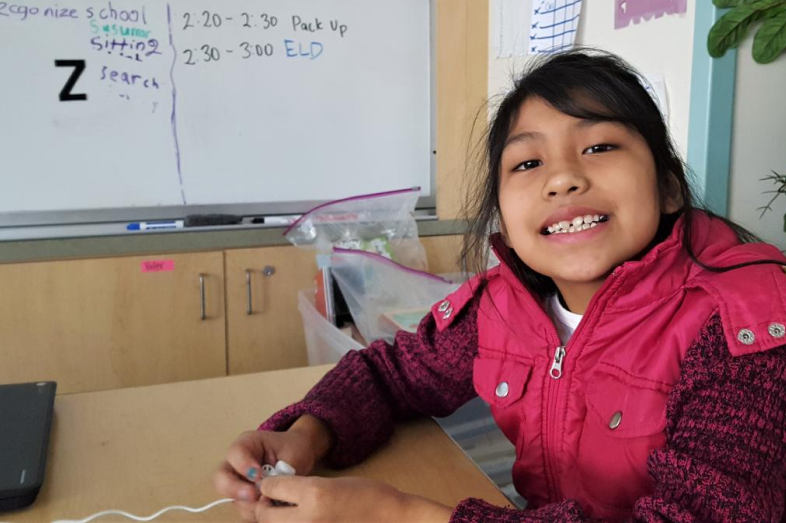

At 10 years old, Audrey Campos is the one who helps her 18-year-old cousin communicate with their grandparents. Unlike her cousin, Audrey speaks Spanish. That’s thanks, in part, to the public school she attends, part of the Camino Nuevo Charter Academy network.

Audrey was in the inaugural kindergarten class for the school’s bilingual program in 2011. She spent 80 percent of her day learning in Spanish that first year, though now Audrey speaks and hears mostly English in school.

Maria Campos, Audrey’s mom, chose this school – the Sandra Cisneros campus in the Camino Nuevo network – over other options in the area primarily for its bilingual program.

“I see kids whose first language was Spanish but they’re losing it,” Campos said. “Right now, we’re living in a country where, if you speak more than one language, you have more opportunities. I want that for my kids.”

Campos’ younger son is in the school’s bilingual program as well. The first grader can already pitch in to help his older cousins communicate with their grandparents. One day, those skills will go on his resume and may make the difference in getting a job.

Responding to Parental Demand

The Camino Nuevo Charter Academy network got its start in 2000 as a product of the Central American community in Los Angeles. After launching a thrift store and other businesses, local parents wanted a school. Ana Ponce, the CEO of Camino Nuevo, said the bilingual model was a direct response to parent demand, and because the school opened as a charter, it could circumvent a laborious waiver process necessitated by the state’s English-only education law that voters approved in 1998 (and just overturned in the November election).

The charter network now has eight sites – an early childhood campus, one K-5 school, three K-8 schools, a middle school and two high schools – each tailored to the specific needs and demands of the neighborhoods they serve. Ponce said most are entirely bilingual, because that’s what parents want, but in neighborhoods like the one that is home to the Sandra Cisneros campus, where there is some demand for English-only instruction, that option is offered as well. At Sandra Cisneros, each grade has two classes in the bilingual program and one class that is English-only.

Camino Nuevo has gained national attention, earning the Bright Spot Award in 2015 from the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics for addressing key educational priorities for Latinos. Its high school has been named among the top 500 schools in the country by U.S. News & World Report, and its various elementary schools have won awards for academic excellence. In general, the network’s bilingual education model has been lauded as a way to better serve English learners and close stubborn achievement gaps between them and their native English-speaking peers.

More broadly, the Camino Nuevo mission statement emphasizes that the schools feature a college preparatory program to prepare youths as critical thinkers, independent problem-solvers, and ”agents of social justice.”

Sheyla Lopez, a 9-year-old fourth grader, transferred into the Sandra Cisneros campus last year. She said her mom wanted her to be able to take classes in Spanish, too. On a recent visit to the school, Lopez sat in a classroom with a faint smell of aromatherapy and gentle music playing in the background while she composed an essay in Spanish about her favorite sports.

The aromatherapy and musical soundtrack are part of the school’s focus on mindfulness. Each classroom has a Peace Place, where students can center themselves before returning to a lesson. The space is stocked with “TheraPutty” and kids can read encouraging letters their classmates wrote in advance.

Principal Melissa Mendoza says the strategy has helped reduce the number of students getting sent out of the classroom for disciplinary infractions.The Sandra Cisneros campus also practices restorative justice. Every Friday morning, teachers specially trained to lead circles focused on building community in their classrooms and addressing any disputes or discipline issues that may have come up over the course of the week.

Staff members are three years into training on trauma-sensitive teaching, too. A full-time psychologist and 10 interns from the University of Southern California offer support to the students who qualify. Fully 14 percent of the student population this school year at the Sandra Cisneros campus is homeless and 96 percent, qualify for free or reduced-price lunches.

A Family Affair

A full-time parent coordinator spearheads the school’s efforts to reach out to students’ families. Recently, for example, the school brought in immigration lawyers to counsel parents worried about deportation, dieticians have helped them learn more about nutrition, and parenting classes have given families tips to use at home. Also, a book club in January drew 60 parents network-wide to discuss Dying to Cross by Jorge Ramos, despite unseasonal rain.

Mendoza sees the investment in parent support critical to ensuring students are ready to learn each day.

“If we don’t work with the parents, whatever trauma is causing that anxiety won’t go away,” Mendoza said.

Almost all of the Sandra Cisneros staff members speak Spanish. Most have bilingual credentials, though some are hired with strong Spanish-language skills and supported to get the bilingual credential from there.

Students – those in the bilingual program and not – see the value of speaking languages other than English every day. Signs are posted around the school in Spanish and no one thinks language acquisition needs to stop at two languages.

Audrey, for her part, is already thinking about learning French and maybe Portuguese.