Games might provide a better way for teachers to figure out what students know.

Some say this playful format can provide teachers with serious information if the games are intentionally designed to assess learning. This can be used to develop a more nuanced portrait of a student’s skills. And sometimes students don’t know they are being tested.

“We try to set up a sting operation to figure out what you know,” said Michelle Riconscente, of GlassLab, an organization that helps with the development of educational games.

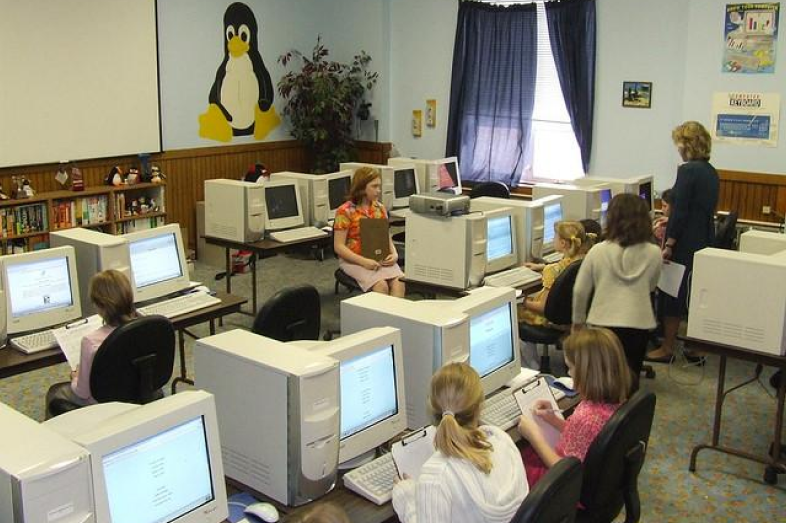

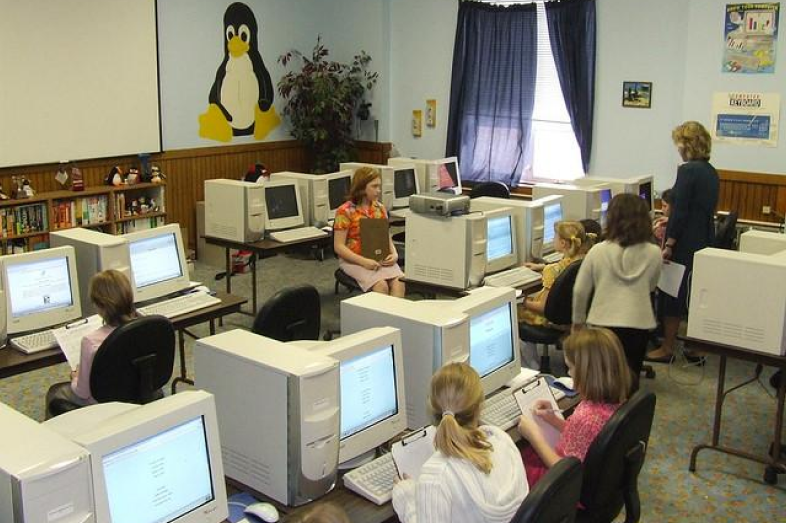

The question of how games can be used to help assess teaching and learning was part of an Education Writers Association seminar on Nov. 18 at Stanford University. Teachers can use games to gauge how well a student is progressing. And students often like playing computer games, so this format offers teachers a window into how students behave when they don’t know they are taking a test.

Teachers don’t have to wait until the end of a lesson to determine what a student knows. Check-ups during a course determine how students are progressing during the lessons. Unlike exams after the class or unit is finished, these types of assessments provide information that can help educators tailor lessons to student needs. Teachers can subtly weave this practice, known as formative assessment, into lessons.

One example of how this works is a game developed by researchers at the AAA Lab at Stanford University. A presentation about this work was offered by Doris Chin, of Human-Sciences and Technologies Advanced Research Institute at Stanford University and Kristen Pilner Blair, of Stanford University Graduate School of Education. Computer games can be designed to measure critical thinking.

“When you put them in a situation, what choices do they make?” Chin said.

One of the games designed at AAA Lab requires players to create a creative poster. (Journalists at the EWA event gave the game a test run.) It provides a speedy check-up on a child’s skills. The game was similar to a choose-your-own-adventure book. Students pick what kind of event they want to promote and the information they want to include on the poster. A motley crew of talking animals judge the posters. At this point in the game, a child picks three animals to review the poster, and the student decides if she wants negative or positive suggestions from the character, and the child can choose to amend their work based on this feedback. Then the student submits the poster for a final score.

Researchers gather data on what steps the player took to arrive at the end. This is assessing the soft-skills of a child, such as persistence and ability to accept a critique of their work. They might also find out if these skills are connected to a child’s score on academic achievement exams. Early, unpublished research suggests children who opted to follow a path in the game that gave them a poster critique with a more critical tone were more likely to score higher in math class.

Games are only effective as assessments if the measurements are valid. And the games must have an engaging design, and they must provide teachers with useful information.

“It’s no good to create really cool stuff if it doesn’t get uptake,” Riconscente said.