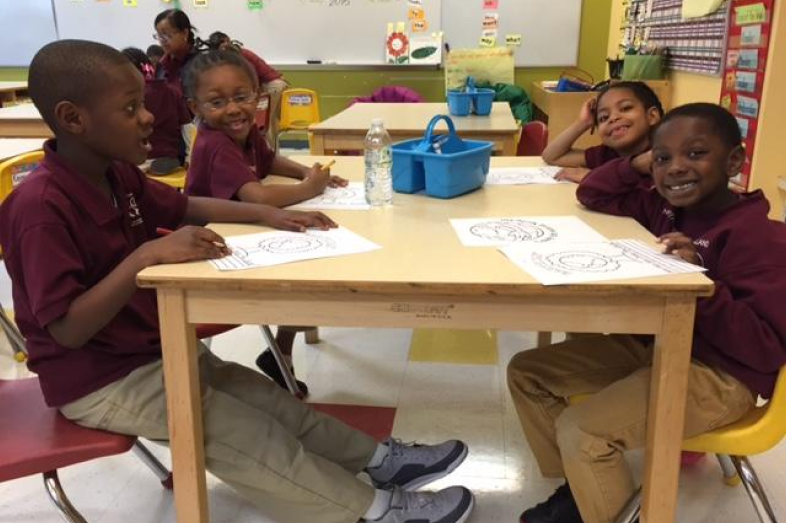

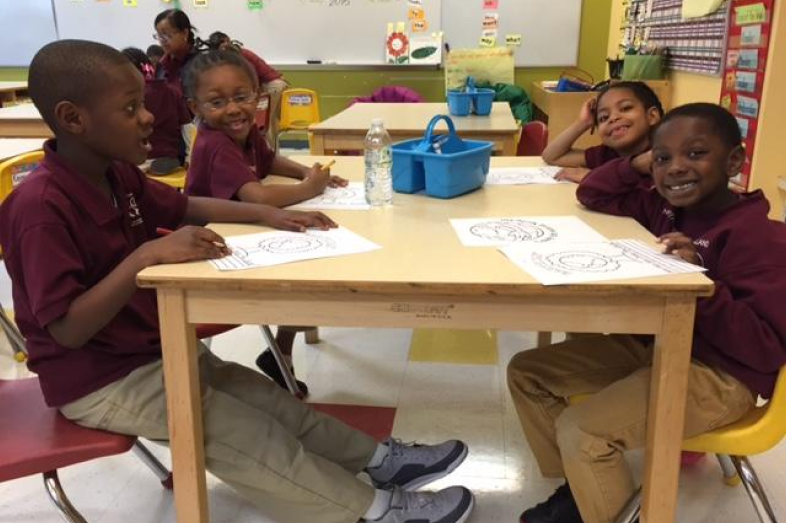

What’s most notable about the Chicago kindergarten class where assistant teacher Nichelle Bell is temporarily in charge is what is not happening. Teachers are not redirecting pupils, who are not off-task. Hands are not in other people’s spaces. Voices—those of children and adults—are not raised.

According to conventional wisdom, there should be bedlam in the classroom here at this charter school operated by the University of Chicago. The teacher of record is on maternity leave and her replacement has had to step out to attend to a student who had a serious medical issue. That’s left Bell and a paraprofessional overseeing reading instruction—arguably the most important period of the day—for the other 33 students at this high-poverty school.

One boy in a small group working on a white board can’t hold still between his turns. While other kids are at the board, he marches up and down the rug at the front of the room. But when it’s his turn again, his focus is intense.

It doesn’t look like Bell is doing much, but in fact the scene is the result of careful planning by her and the rest of the kindergarten team The kindergarteners working calmly in small groups are in fact wholly engaged by the activities at the literacy stations set up around the room.

In addition to the white board, known here as the writing center, there’s an ABC center, a tongue-twister center, a poetry center and even a literacy post cleverly disguised as an art center. The adults know which kids need to polish particular concepts or skills. Accordingly, each small group’s progression is posted on a bulletin board.

Welcome to the North Kenwood/Oakland (NKO) campus of UChicago Charter, the University of Chicago’s four-site charter school, a nationally recognized model for systemic school improvement. One of two programs serving pre-kindergarteners through fifth-graders, NKO – founded in 1998 — is one of Chicago’s highest-performing non-selective schools. (A group of education journalists visited the school site as part of the Education Writers Association’s National Seminar, held recently in the Windy City.)

By the Numbers

In 2012, 86 percent of NKO’s students met or exceeded Illinois state standards overall; 92 percent met or exceeded math and science goals. Its fourth- and fifth-graders outperformed their peers across the country on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Almost all are African-American and 83 percent are from low-income families.

NKO offers a full-day preschool for 4-year-olds and works with the Chicago branch of the well-regarded early childhood program EduCare to encourage parents to see NKO and UChicago’s other pre-K-5 campus, Donoghue, as desirable options. There are four to seven applicants for every seat in the lower grades. Admission is done by lottery.

Thanks to a series of strategies identified in conjunction with researchers at the university’s Urban Education Institute (UEI), the overwhelming majority of kids in UChicago’s lower grades will leave its middle school on track and graduate from its high school.

In 2012 and 2013, every graduate was accepted to a four-year college and more than 90 percent enrolled. That enrollment rate is the second highest in the greater Chicago area.

A National Model?

Having an impact on the national discussion about urban education is part of the school’s mission to create a “Pre-K to 12 superhighway” which cultivates critical thinkers and leaders. The school’s approaches were chronicled in the 2014 book “Restoring Opportunity,” an examination of three programs that have proven transformational over time and on a large scale.

The strategies—including the system of collecting data that helped assistant teacher Bell and her colleagues route students to different literacy stations—are also being shared with schools elsewhere. Seven schools in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area, for instance, began using some of the methods in 2012 and are seeing steady gains in early reading proficiency.

Teachers from the Minnesota schools have had the opportunity to visit UChicago and UEI experts have been contracted to provide ongoing coaching to the schools that are trying to replicate the program’s success.

UChicago’s leaders believe five factors must be present for a school to successfully serve students in poverty. Leaders must be effective and teachers must work collaboratively. The school must have a climate of high expectations and strong instruction. Families must be engaged.

If a school does well in three of those five areas, research has shown it will be 10 times more likely to improve student performance than its neighbors, said UChicago CEO Shayne Evans.

“Young people are smart,” said Evans. “They know if you don’t grade their homework. They know if you only get through the first five paragraphs of their essay.”

By his lights a strong leader is the most effective of the five values. High expectations on the part of the school’s top educators trickle down into the other four areas.

Teacher Collaboration

What those values look like in practice is crystal clear to Bell, who has worked at NKO for four years and is in college studying for a teaching credential. She and the other kindergarten educators plan and review instruction at the beginning and the end of each day, and they join the rest of the program’s faculty for weekly professional development.

What Bell was in fact doing in the kindergarten classroom was observing to see how well pupils in one of the groups were engaging in “phonemic segmentation”—the practice of breaking words down and sounding out the parts.

On Wednesdays, NKO dismisses students at 1:00 p.m. so teachers can work together from 2:00 to 4:00. This particular lesson–decoding words–was on the agenda for that afternoon’s study time for the adults.

The school uses a literacy tool developed by UEI to help teachers both determine where each student is and how to plug gaps in understanding. Three times a year, students take a formative assessment developed by university researchers called the STEP, short for the Strategic Teaching and Evaluation of Progress.

The researchers determined that there are 12 separate skills, or steps, a student must acquire to read fluently by third grade, the point at which literacy becomes crucial for academic success in any area. The quizzes show how many of the steps a student has mastered, but more crucially gives the teacher specific strategies for supporting the student.

It sounds simple, acknowledged Tim Knowles, the chair of UEI. But even schools that encourage teachers to use formative assessments often fail to help them figure out what to do once a gap has been revealed.

Even though she is a classroom assistant, Bell is able to analyze her kindergarteners’ STEP data and to design lessons that are as personalized as possible. If a student is off-task or resisting redirection, she asks for suggested alternatives to engage them.

“We try to redirect privately and praise publicly,” she said.

“We talk a lot here about not blaming the child,” Evans added. “We talk about adults being the owner of their classroom. If someone is not engaged, what are the adults needing to do?”

Early Interventions

The charter has developed other methods to prevent early problems, from turning into the kinds of gaps that can keep a student from graduating from high school or persisting in the less structured setting of college.

Students are screened going into high school, for example.

“What is most predictive of whether a student will graduate high school is how they do in ninth grade,” said Evans. “Have they passed their core courses and been absent for less than 10 days?”

If the answer is no, UChicago intervenes the summer between eighth and ninth grades. Systemwide, Chicago Public Schools has seen a 27 percent increase in the number of 9th graders on-track for graduation.

“We have not seen slippage as kids go into 10th, 11th and 12th grades,” said Evans.

So what does a school like UChicago aim for, when 100 percent of its graduates are admitted to college? Evans has ready answers: How about a 100 percent college completion rate followed—set the bar high, now—by acceptance at more highly selective colleges.