A new report offers an unprecedented look at the testing load in large urban districts across the nation, finding considerable redundancy and a lack of coordination among the exams.

Students typically spend about 20 to 25 hours per year on roughly eight mandatory assessments, according to the analysis and testing “inventory” by the Council of the Great City Schools. The report included exams that fulfill federal requirements, as well as other mandated by states or local districts.

In reaction to the new analysis, the Obama administration on Saturday offered a high profile pitch to reduce testing, including by urging states to require a 2 percent cap on classroom time devoted to taking such exams. It also outlines other steps, including a call to ensure the tests are high quality, fair to kids with learning challenges, including special education students and English language learners, and — perhaps most importantly — are just one measure of a student’s knowledge and progress.

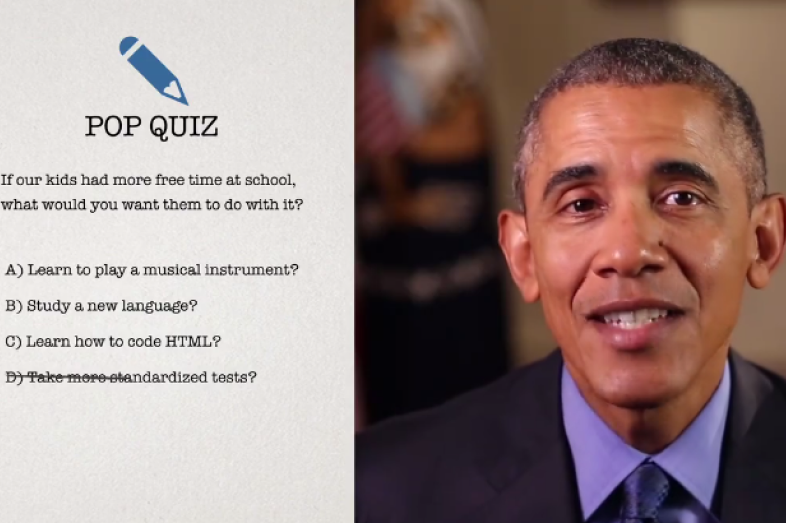

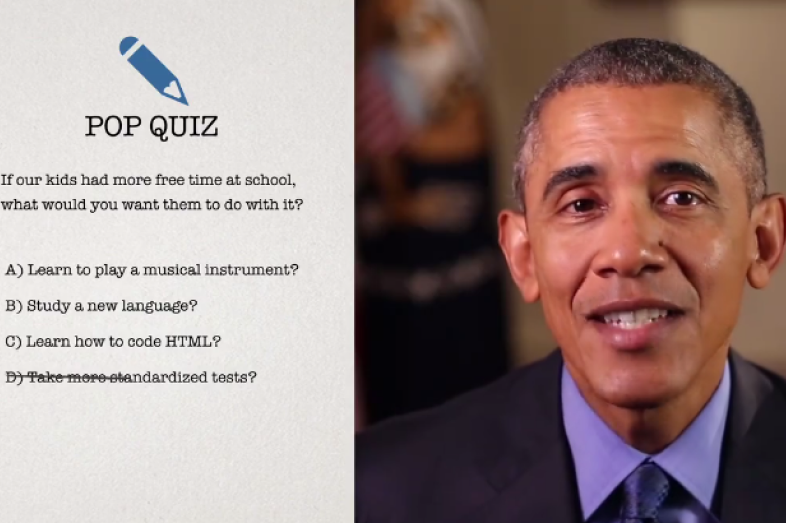

In a video posted on Facebook, President Obama said that ‘‘Learning is about so much more than just filling in the right bubble. So we’re going to work with states, school districts, teachers and parents to make sure that we’re not obsessing about testing.’’

The White House announcement and the new report have drawn widespread attention in the news media, including a piece by Kate Zernike for The New York Times. She writes:

“Faced with mounting and bipartisan opposition to increased and often high-stakes testing in the nation’s public schools, the Obama administration declared Saturday that the push had gone too far, acknowledged its own role in the proliferation of tests, and urged schools to step back and make exams less onerous and more purposeful.”

Arne Duncan, who steps down as secretary of education in December, told The New York Times that he has “no question that we need to check at least once a year to make sure our kids are on track or identify areas where they need support … But I can’t tell you how many conversations I’m in with educators who are understandably stressed and concerned about an overemphasis on testing in some places and how much time testing and test prep are taking from instruction.”

The announcement is not a complete surprise. As Education Week’s Andrew Ujifusa noted, states have already been taking action to address concerns about over-testing. And at EWA’s National Seminar in May, Duncan reiterated his position that testing had gotten out of hand.

The new report from the Council of Great City Schools (representing the nation’s largest districts) finds that, on average, students take over 110 federally, state, or locally mandated assessments between kindergarten and 12th grade. At the eighth-grade level, where the testing load is the highest, test-taking accounts for 2.34 percent of the student’s instructional time.

The report makes clear that semantics matter when talking about assessments, which have grown increasingly controversial in recent years as grassroots “opt out” movements have gained momentum. The CGCS report found that “parents want to know how their own child is doing in school, and how testing will help ensure equal access to a high quality education.” From the report:

“The sentence, “It is important to have an accurate measure of what my child knows.” is supported or strongly supported by 82 percent of public school parents in our polling. Language about “testing” is not.”

Among the other key findings:

- Among the 66 districts surveyed by CGCS, over 400 different assessments are being used. According to the report, “some tests are not well aligned to each other, are not specifically aligned with college- or career-ready standards, and often do not assess student mastery of any specific content.”

- Teachers often wait as long as four months to get the results of assessments, which limits their usefulness in guiding instruction or helping individual students improve. And in many districts spring test results are not returned until the fall, when a new academic year is underway.

- “There is no correlation between the amount of mandated testing time and the reading and math scores in grades four and eight on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP),” according to the report.

“Everyone is culpable here,” Michael Casserly, the executive director of the Council of the Great City Schools, told the Washington Post’s Lyndsey Layton. “You’ve got multiple actors requiring, urging and encouraging a variety of tests for very different reasons that don’t necessarily add up to a clear picture of how our kids are doing. The result is an assessment system that’s not very intelligent and not coherent.”

Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, praised the White House’s announcement, and noted that it’s consistent with perceptions among the public that testing in schools has gotten out of hand.

“This is common sense,” she said in a statement. “It’s why overwhelming numbers of Americans think there is too much testing, as seen in the recent Phi Delta Kappa/Gallup poll, and it’s why legislators on both sides of the aisle want to fix No Child Left Behind, a law that drove over-testing. The time to act is now.”

It was the Obama administration’s acknowledgement of the part its education initiatives have played in pushing testing to the forefront that caught my attention. From the official announcement:

“No one set out to create situations where students spend too much time taking standardized tests or where tests are redundant or fail to provide useful information. Nevertheless, these problems are occurring in many places—unintended effects of policies that have aimed to provide more useful information to educators, families, students, and policymakers and to ensure attention to the learning progress of low-income and minority students, English learners, students with disabilities, and members of other groups that have been traditionally underserved. These aims are right, but support in implementing them well has been inadequate, including from this Administration.”

But Bob Schaeffer, the education director of the advocacy group FairTest, which has been sharply critical of the amount and uses of standardized testing, told me in an email Saturday that the White House doesn’t go far enough in acknowledging its culpability.

It’s “far too little genuine test reform,” Schaeffer said. “Coming far too late.”

For the latest coverage and research, as well as essential background, take a look at EWA’s Topic Page on Standards and Assessments. We also had a series of regional seminars on covering the Common Core in the era of standardized tests. You can find videos, podcasts, and write-ups from those sessions here.