For students looking for greater flexibility in their learning environment, virtual schools can be a better option than a traditional bricks-and-mortar K-12 campus. But some online programs operating in more than two dozen states have come under scrutiny for reaping profits while yielding poor academic academic outcomes.

Three education experts talked about the accountability challenges facing the virtual charter school sector during a panel at the Education Writers Associations’ Charters & Choice Seminar in Denver in February. They also discussed trends in online education more broadly, including state-run programs such as the Florida Virtual School and a growing number of district-sponsored online offerings.

Kevin Welner, an education professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, and the director of the National Education Policy Center, said the struggles seen at virtual charter schools goes beyond finances and academic results. It’s also a matter of how well a student fits in with the new environment.

And in Colorado, there isn’t much financial incentive to keep kids enrolled: millions of dollars go to virtual schools even after students drop out, Welner said.

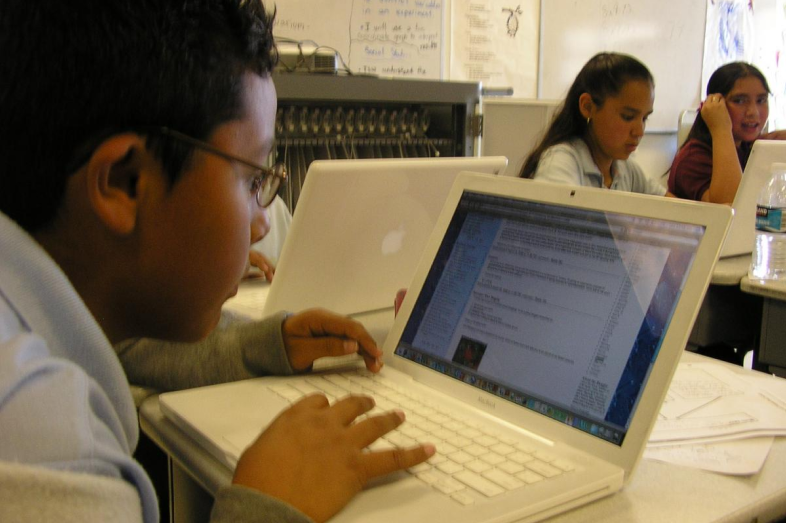

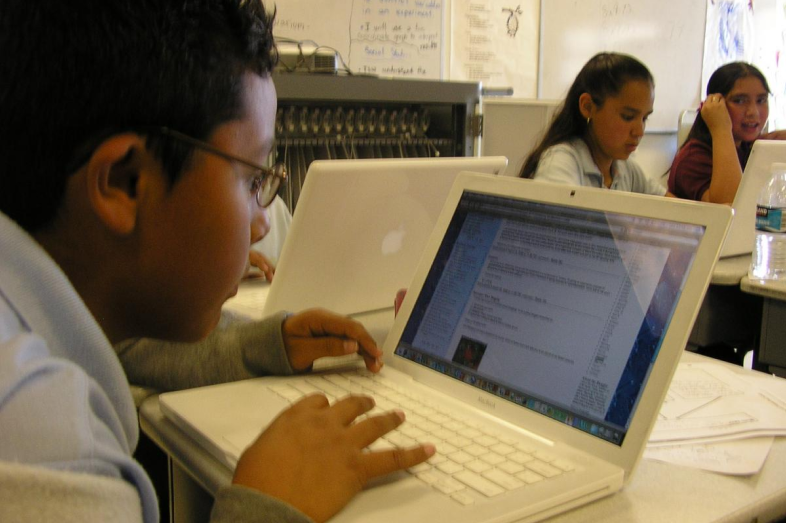

“If we are talking about a pure online school or course, where the student is at home with a computer and no good adult guidance, why in the world would we expect this to work with students who struggle academically?” he said.

Virtual Enrollments Still Small

While virtual school enrollment grew steadily across the nation until last year – when enrollment was flat due to changes in Florida – the total number of students remains small.

About 3 percent of students attend a virtual school in the states that allow them, and enrollment grew by about 6.2 percent between 2013 and 2014.

Connections Academy, which was acquired by the British publishing giant Pearson several years ago, serves about 70,000 students. The company’s biggest competitor, K12 Inc., enrolls about 200,000 students. (Both Connections and K12 are forprofit companies.)

Mickey Revenaugh, the co-founder and executive vice president of Connections Learning, which runs online schools through Connections Academy, said parents who put their children in an online school are looking for flexibility.

Their child may be bullied at school and are in search of a safer environment, or their child may be training for the Olympics and need to take classes outside typical school hours, she said.

“This is a pretty radical choice for parents to make, to take their child out of a brick-and-mortar school … and go to a virtual school,” Revenaugh said.

Outdated Laws?

John Watson, the CEO of Evergreen Education Group, said 26 states have some form of virtual school or academy. Within that group, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Michigan and Virginia have made taking an online course a graduation requirement for high school students. Evergreen publishes an annual review of policy and practices in online education, “Keeping Pace With K-12 Online and Blended Learning.”

Teachers in many of those states are looking for innovative ways to use the flexibility provided by online schools or classes, but they’re running into challenges, Watson said.

In most cases, virtual programs are created under charter school laws that do not account for the needs of a school without a physical building.

“They’re operating under laws that were passed before virtual schools existed,” he said.

Revenaugh said the Connections Academy schools have to meet the same academic accountability measures in each state as a traditional brick-and-mortar school.

Connections Academy students tend to do better than students in traditional schools in English language arts and exceed the national average on the SAT, she said. But Connections Academy students struggle on math when compared with their state peers, Revenaugh added. The charter operator is making a concentrated effort to raise math scores by tailoring instruction plans to meet each student’s needs, she said.

While some people think virtual schools provide little interaction between student and teacher, Revenaugh said teachers are watching data and interacting with students daily. The average teacher at the virtual school has 11 years experience, according to Revenaugh.

“The teachers are really kind of the secret sauce in our world at Connections,” she said.

There are still challenges on the accountability front, Welner said.

In Colorado, K12 Inc. lost the charter for its virtual school heading into the 2014-2015 school year, but quickly found another authorizer willing to oversee them in the state.

K12’s first charter was revoked due to low graduation rates and financial mismanagement, according to media reports.

Transparency Questions

Colorado is not alone in its challenges. Similar problems have popped up with virtual schools in states across the nation.

“There’s accountability but there is the related issue of transparency,” Welner said. “I would say the issue of transparency, financially and otherwise, is huge in this area.”

Welner also said people should pay attention to the amount of advertising virtual schools do, especially compared with traditional schools. (In 2012, he estimated that K12 was spending about $340 per student on advertising.)

Watson told the EWA audience that virtual schools need to advertise because the concept is still new, and few parents know about the choices available. Even schools offering their own courses are looking for ways to reach out to students and parents, he added, including making radio ads and hanging up banners.

“We worked with a number of school districts that have started online or blended schools,” he said. You have to advertise this or no one will show up.”