Imagine taking an English class with a teacher who struggles with writing and grammar.

That’s the type of instruction many students in Miami-Dade County Public Schools were getting in Spanish class, where teachers with Hispanic last names who spoke Spanish well enough to get by were being thrust into a role they weren’t trained for, according to recent articles by Christina Veiga of the Miami Herald.

The district announced this week that it would seek to rectify the problem by rolling out a new graduate certificate program for teachers, among other solutions to enhance the quality and quantity of Spanish instruction for students living and learning in one of the country’s most bilingual cities.

Veiga wrote an article in May that highlighted the school district’s bilingual education problem:

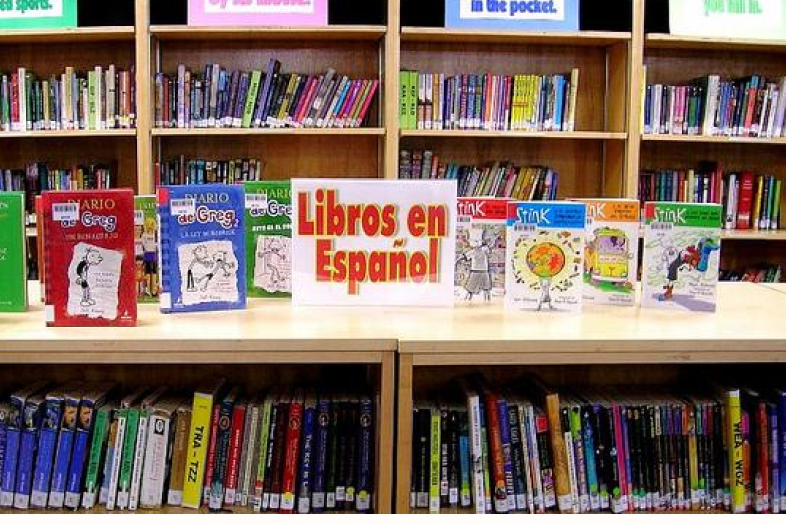

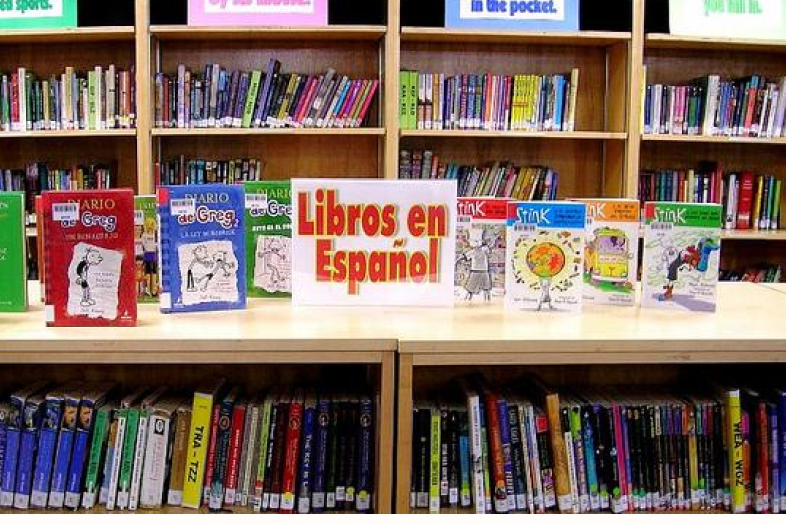

On the nightly news, in the halls of government and in the aisles of the supermarket, Miami-Dade County speaks español. But how well today’s schoolchildren read and write in Spanish – the real measure of fluency in an increasingly competitive economy — has become a matter of debate as the Miami-Dade County school system reconsiders how to teach children the native tongue of many of its residents.

The district cut elective-type Spanish classes in 2013 and moved to an immersion-based model, where students took core courses in both English and Spanish. In theory, immersion would better produce bilingual students, but the elementary teachers — who were qualified to teach multiple subject areas — were not trained to teach a foreign language.

“I’ve just kind of been winging it,” one teacher told Veiga. She grew up speaking Spanish only at her grandmother’s house — a scenario typical of many second- and third-generation immigrant families. The teacher admitted to looking up words in a Spanish dictionary and fretting over accent marks when sending letters home to her students’ native Spanish-speaking parents. “I feel like [the students] deserve much better than that.”

Veiga reports that the school district will partner with Florida International University as early as this fall for classes designed for teachers to build fluency in Spanish and learn how to effectively teach a foreign language.

The district will also put money into revamping its curriculum – which includes new textbooks — for a more bilingual, bicultural approach and appoint a task force to research and recommend best practices.