Colleges Face a New Reality, as The Number of High School Graduates Will Decline

An increase in low-income and minority-group students will challenge colleges to serve them better

An increase in low-income and minority-group students will challenge colleges to serve them better

The nation’s colleges and universities will soon face a demographic reckoning: A new report projects that the total number of high school graduates will decline in the next two decades, while the percentage of lower-income and nonwhite students will increase.

The report challenges colleges to increase the percentage of students from all demographic groups entering college and earning degrees. While more students in recent years have been enrolling in postsecondary institutions, the U.S. has struggled to enable more to graduate with a bachelor’s or associate’s degree. According to one respected tally, just under 55 percent of students who entered college in 2010 had earned degrees after six years – an increase of two percentage points since 2009.

For higher education institutions to continue at that pace or boost it, they’ll need to find new ways of educating a student body increasingly composed of people who are the first in their family to enter college. And because those students tend to have fewer financial resources, colleges may feel pressure to expend more resources to help students handle the costs of college.

“Well prepared, well resourced, full-pay students: Those are the students all institutions want because they help them meet their bottom line,” said Joe Garcia, president of the organization that released Tuesday’s report, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. “But there are fewer and fewer of those students as a percentage of the total.”

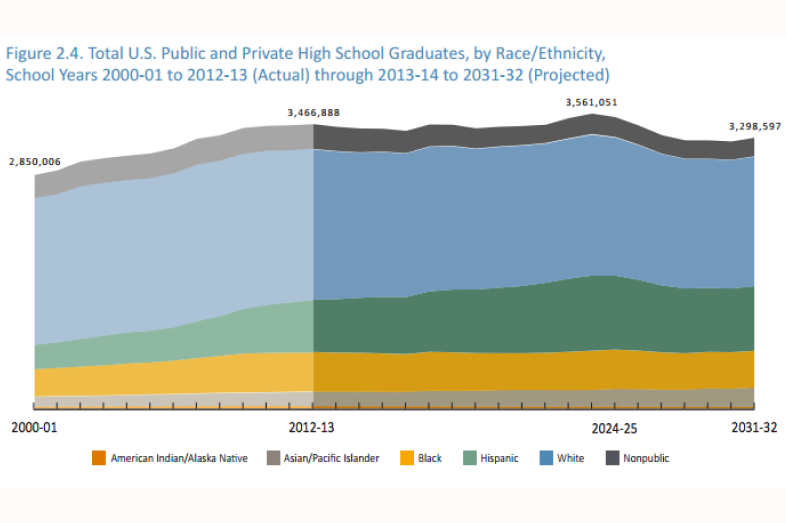

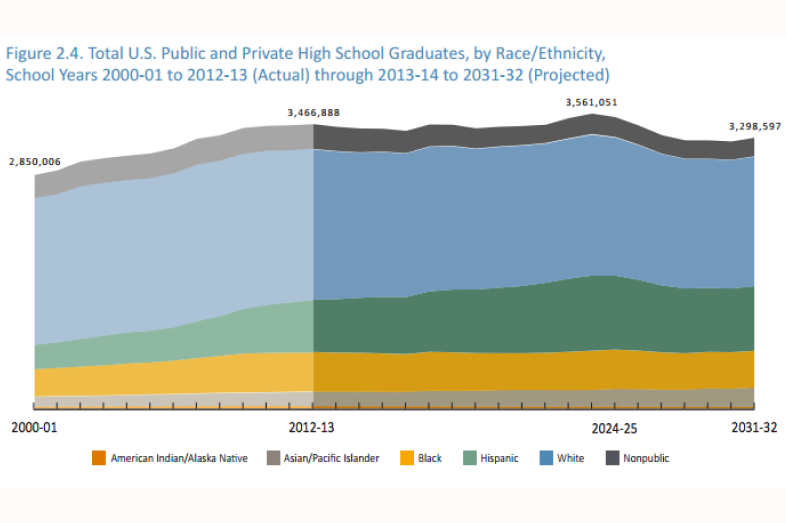

Though the country’s number of high school graduates grew by 30 percent between 1995 and 2013, to 3.47 million students, by next year colleges will see a high school graduating cohort that is smaller by 81,000 students – a dip of 2.3 percent. After a few years of some growth, the report projects that from 2027 to 2032 the annual graduation totals will each be smaller by 150,000 to 220,000 people than the ones the nation had in 2013.

Fueling the decline will be decreases in the overall student population and growth among specific student groups. According to the report:

“Graduation rates have not dipped” in the projections, Demaree Michelau, one of the report’s co-authors, wrote in an email. The projected enrollment declines are “related to overall declines in births and student enrollments in K-12.”

Regions will show wide differences in graduating high school students, the report forecast. Southern and western states, which combined already represent 72 percent of the nation’s high school graduates, will increase their share by a few points in the next two decades – though the total number of graduates in western states is anticipated to dip. The Midwest, however, is set to lose 93,000 graduates – a decline of 19 percent. Similar projections are forecast for the Northeast, which is slated to lose 72,000 graduates.

In Texas, which the report considers a southern state, only 56 percent of high school graduates go to college. “It’s a number that has to increase tremendously,” said William Serrata, the president of El Paso Community College. The national average is nearly 70 percent.

Serrata said some innovations have been shown to help. For example, students in dual-enrollment courses, which allow high school students to take college-level courses for course credit, enter a postsecondary institution 80 percent of the time in the El Paso area. That’s 30 percentage points higher than students who don’t enroll in dual-credit classes.

Policymakers and university presidents “should not come away with the sense that this is hopeless, that institutions are going to close, and that we’re not going to meet our workforce needs,” began Garcia. But, he added, “if institutions continue to do the things they’ve always done, but with a different population, they’re going to have worse results, lower enrollment, and they’re going lose them to other institutions that are more forward-looking and more progressive.”

Garcia also cautioned that the report shouldn’t be used to censure universities that are increasing capacity for additional students. California, for example, is enduring a space crunch due to the popularity of its colleges, and is so far behind in providing seats for students that the prospect of a downturn in high school graduates won’t allay the current building boom, he said.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about higher education.

Your post will be on the website shortly.

We will get back to you shortly