As tuitions swell and student loan debt climbs further, one aspect of higher education that has been overlooked is the recipe required to transform a college education into a set of skills that prepares students for the workspace.

As it turns out, neither colleges nor employers have a firm grasp on what flavor that special sauce should have, reporters learned at “The Way to Work: Covering the Path from College to Careers” – the Education Writers Association’s seminar on higher education held in Orlando Sep. 18-19.

Years ago, “if you had a fine, rigorous liberal arts degree from one of the nation’s colleges or universities, you found your place in the economy,” said Grant Cornwell, president of Rollins College in Florida, during a session at the conference. Now “I am sure that that is not true anymore.”

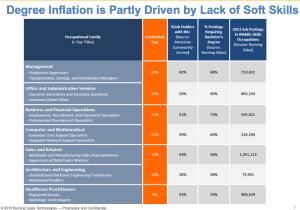

Recent job market analysis by leading labor research firm Burning Glass has shown that employers increasingly are requiring job seekers to have bachelor’s degrees even when the positions don’t necessarily call for them. In an analysis of 2.3 million positions that range from business management and administrative workers to training and computer network specialists, two-thirds of the new job postings required a bachelor’s degree even though fewer than half of workers currently employed in those positions attained a bachelor’s.

The top four positions represent more than 2 million jobs and suggest where degree inflation is most pronounced. (Source: Burning Glass)

Burning Glass researchers went one step further by comparing the job postings for positions that didn’t require a bachelor’s degree to those that did, finding that the expectations between the jobs didn’t vary. “What employers are doing is proxying for foundational skills,” said Matt Sigelman, CEO of Burning Glass. Employers are “paying a lot extra to get those bachelor’s degrees, and they’re making those jobs a lot harder to fill.”

By foundational skills Sigelman means the soft skills that typically are associated with a liberal arts education, like the ability to accept feedback, work collaboratively, and manage one’s time.

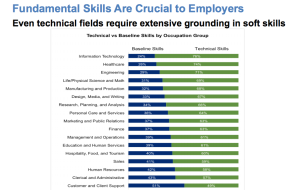

Even job postings for technical positions regularly ask for those foundational skills. For example, among listings for engineers and manufacturers, nearly a third of the requirements fall under soft skills.

Even highly technical positions stress soft skills. (Source: Burning Glass)

Nevertheless, some workforce experts say that liberal arts education in its current form is insufficient for many of the jobs out there, with the unemployment rate for such graduates twice as high as those with degrees in math or engineering. Liberal arts majors can expand their employment prospects by acquiring popular technical credentials, like building databases or website maintenance, that would double the number of job positions for which such majors are eligible, said Sigelman, though getting the message out to colleges that these credentials are valuable has been a challenge.

In fact, a fifth of jobs demand a certification in addition to a bachelor’s degree no matter the concentration, Burning Glass research shows. And not just any certification will suffice – of the thousands of credentials that require less commitment than a bachelor or associate’s degree, just 200 were what more than 2 million job postings requested in the past 12 months.

“When we talk about the workforce, it’s such a challenging conversation because the word is too broad and so there are workforces and sub-economies,” said Sandy Shugart, president of Valencia College, a community college in Orlando recognized as one of the nation’s best at graduating a diverse student body that is prepared for the job market.

While it’s true a Georgetown University study predicts that 65 percent of jobs by 2020 will require a postsecondary education, that could mean a certificate, associate’s or a bachelor’s degree.

Shugart dislikes the current structure for higher education instruction, in which students fulfill liberal arts or general education requirements their first two years and begin studying toward their concentration only in their third year. It’s a model that he says asks students to “defer [their] gratification long enough and stay in school long enough” before they explore the thing that interested them in the first place. That approach “is just upside down,” Shugart said. What works for one sector of the economy may not work in another, and in many instances, full bachelor’s degrees might thwart the labor market potential of students.

Instead, Shugart would like to see more postsecondary programs in which work experience is thrown into the mix earlier in the academic process. Shugart argues that, from a student motivation perspective, “no class will ever replace work as a place of learning, and we still haven’t mastered that in our education model.” Increasingly, work experience before attaining a degree can determine whether a newly minted graduate gets hired. Sigelman of Burning Glass points to his company’s research that found significant overlap in the expected skills found in internship and entry-level positions.

The interplay between work and academics is more fluid for middle-skilled technical positions, like those in machinery, health and construction. Shugart said that in his experience, multiyear academic programs don’t cut it. What does work is a series of certificates that can each be attained in a month or two and be bundled or “stacked” together, in higher ed jargon. Employers have a high demand for employees who can start work out of the gate but grow with the position, earning a new credentials the longer they work. It’s a strategy that moves students, almost always those that attend a community college, “from $10 an hour to $12, and then from $14 to 18, and at some point, they might reach a point where [they’re in a] position now to support a different kind of education,” Shugart said.

That approach has its challenges, too, though. Sigelman says only large employers are able to signal to colleges the types of certificates that they find most useful and can develop a worker’s potential in the company. But most jobs are at smaller companies that lack the resources to flesh out their human capital needs and are less likely to forecast to local colleges the skills they’ll need future graduates to possess.

Which brings us back to Cornwell of Rollins College. If most employers can’t determine the attributes they find most valuable, students should be educated with a more comprehensive curriculum that relies on the liberal arts model, he asserts. That’s not to say every student should walk away with a course credit in Shakespearian sonnets. Rather, he views higher education’s new mandate as one in which graduates “know how to represent and talk about the skills that they’ve acquired and match them with the career into which they are entering.”

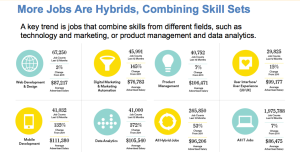

There’s data to support that perspective. Burning Glass research suggests the degrees that are most valuable to employers are ones that allow employees to combine skills from different fields, such as product management and data analytics, and synthesize information from a wide array of resources.

Employers increasingly value skills that enable workers to fuse ideas from a diverse set of sources. (Source: Burning Glass)

Sounds like a solid term paper, doesn’t it?