Civic duty comes in many forms.

Ask Jimmy Gallivan, a junior at Somers High School in Lincolndale, New York.

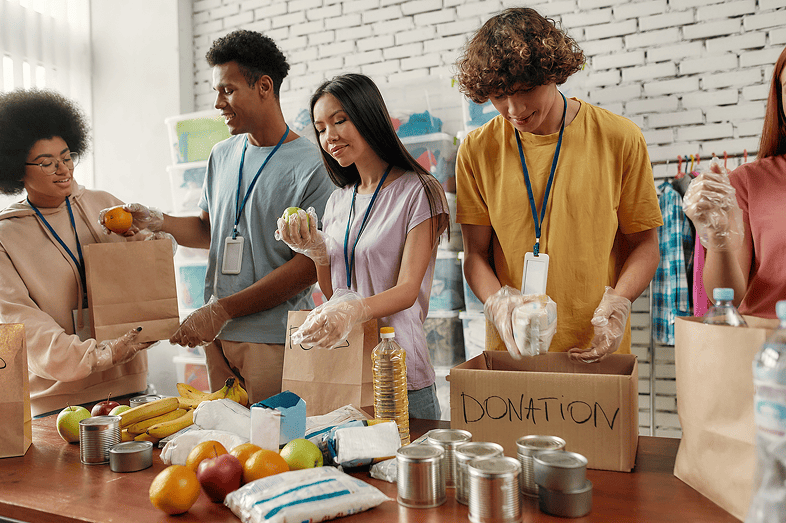

Gallivan is a civics enthusiast: He is trying to launch a civics club at his school; he’s a student council member, and recently, he traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet with members of Congress to advocate for improved education funding. He believes civics is a broad term: Doing one’s civic duty can include volunteering at a local food bank, he said. It doesn’t always mean wading into polarizing political debates.

“It’s not just going and talking to elected officials … Civics is a huge field, and that encompasses a lot of things, that of being involved in your community,” he said.

Civics education is a bedrock of public education in the United States. But it’s often misunderstood, experts and advocates said. It’s also increasingly caught up in modern debates over classroom subject matter; some policymakers have moved to limit the way students engage in civics education. Republicans in particular have increasingly opposed the concept of action civics, a concept that encourages students to participate in democratic processes, according to the University of Southern California. Instead, they’ve pushed civics education that promotes values legislators have characterized as “patriotic,” celebrating democracy contrasted with other forms of government.

Media literacy, often wrapped into civics education, has been under fire, too, at a time when misinformation has proliferated on platforms students frequent, such as TikTok and Instagram.

Journalists should try cutting through the politics to portray the core mission of civics education: Instilling a sense of responsibility to community in children and young adults.

Educators say teaching students to become informed, engaged citizens means rising above temporary discomfort when taking on divisive topics. And while there is contention over how civics should be taught, there’s little disagreement over its value in the classroom.

“There are lots of different perspectives on how to teach civics, but there is consensus that civics matters,” said Verneé Green, CEO of Mikva Challenge, a Chicago-based nonprofit that encourages youth civic participation through educational programs, curricula and teacher training.

A Quick Explainer on Action Civics

Action civics is a concept that’s come under fire politically more recently. Here’s a quick recap of the controversy:

Defining action civics: Action civics is project-based learning, which encourages students to engage in democratic issues directly. In one program often cited in research, Generation Citizen, a class chooses to focus on one issue and develop an action strategy, according to research through the National Council for the Social Studies.

What it looks like: In one example from a story in The Hechinger Report, a student argued in a city council meeting for a plastic bag ban. In another event involving Mikva Challenge participants, D.C.youth hosted a mayoral candidates forum in May 2022.

Proponents say: Heather Goodenough, a social studies teacher who now helps other teachers as an instructional specialist with the Oklahoma Council for the Social Studies, said action civics is really about showing students what it’s like to get involved in community issues.

Doug Linkhart, a public policy expert and president of the advocacy organization National Civic League, said that action civics helps students contend with real-life problems and encourages civil discourse.

“It brings kids into the community, and it brings the community to the school so that students are challenged with a real-life topic and encouraged to think about solutions or ways to handle that topic,” he said.

Opponents say: As reported by The 74, conservative scholar Stanley Kurtz – a senior fellow with the Ethics and Public Policy Center – has led the charge on the backlash to action civics. Kurtz has maintained that such programs overwhelmingly encourage left-leaning political action, likening it to what he’s called “indoctrination.”

Action civics, according to Kurtz’s writing, turns “grievance and anger into protest and lobbying” without the proper examination under the guise of civics education, which typically garners bipartisan support.

Kurtz, responding to email questions from EWA, wrote that instead of employing action civics in the classroom, “Debate and debate-themed exercises are an excellent way to create engaged citizens without forcing a particular political perspective on them.”

What the research says: A 2020 study from Baylor University researchers examined four years of data from a weeklong action civics program called iEngage, finding the program increased civic competence among students.

Another 2016 study from University of California, Berkeley researchers looked at data from 617 middle and high school students in 55 classrooms in Generation Citizen‘s action civics program, concluding that the program was associated with positive gains in self-confidence around civics.

State Restrictions on Action Civics

State politicians across the nation have worked to restrict or prevent action civics in schools . Efforts to limit or chill programs around action civics include:

How Educators Approach Creating Engaged Citizens in Divisive Times

Journalists should remember in coverage that civics education competes with core classes, such as math and English, and not every state includes a requirement to teach students civics, according to advocacy nonprofit CivxNow, which tracks state civics requirements.

At least 150 schools in eight states use Generation Citizen as a resource for action civics education, according to the organization. More broadly, 40 states require students take at least one civics or American government course, according to the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

So while civics may take a splashy role in debate at the state level or a school board meeting, reporters should seek to contextualize just how much civics education students receive in their state.

Green’s organization, Mikva Challenge, partners with schools that use civics curricula the organization has developed. Curricula revolves around developing argumentative writing skills, youth activism, frameworks for building a youth governance body at school and more. Mikva also trains educators to lead classrooms in a way that fosters what Green called a “democratic space,” in which student voices are heard.

“That’s a skill to be able to say, ‘OK let me open up this space where it’s no longer the teacher as the only expert in the room, but then there’s expertise across the classroom,’” Green said. “And giving them (teachers) the skills to be able to facilitate the discussion, and giving students the space to be able to talk up and speak up about those issues and share their voices.”

But even when civics discussions become politically charged – and contested – Green said disagreement doesn’t mean educators should pump the brakes on a conversation.

“Some of the skills that are gained are not only speaking up, but also listening and considering, and at the end of some of our events, we’ll say, ‘Did you hear something you didn’t agree with?” Green said. “Giving that space for that listening, for that understanding, even if I don’t agree with you, maybe I’ll understand your perspective differently.”

To Linkhart of the National Civic League, fostering those difficult conversations in civics helps empower students, eventually creating a sense of civic responsibility.

“It’s when a student has an opinion or a question or problem that they come up with, it’s letting them run with it, rather than shutting it down,” he said.

How Media Literacy Fits Into Civics Education

And part of civics education includes encouraging students to make informed decisions about polarizing issues and big-world problems by challenging the information they encounter online. While some states have moved to require media literacy programs in schools, people have led movements to discourage the practice, arguing students are pushed to news sources that push one ideology, namely, left-leaning beliefs.

Kurtz, over email, wrote that he doesn’t support media literacy education “in its current form,” and that such lessons should honestly cover controversies around media bias and “not promote uncritical acceptance by students of mainstream media fact checkers and news sources.”

The American Psychological Association, however, calls for schools to institute “digital literacy” competencies, focusing on helping the younger generation sort fact from fiction as they are susceptible to buying into conspiracy theories pushed on social media.

Goodenough of Oklahoma Council for the Social Studies said classroom discussions around making informed decisions should focus on students, ensuring “that they themselves know how to make informed decisions on their own – we would never want to put thoughts or ideas in their mind.”

Notes for Journalists From the Classroom – 3 Takeaways

- Civics education is about responsibility at its core, Linkhart said. That means students should be instilled with a value system that encourages everything, from obeying laws to standing up to bullying. Good civics education should help students navigate the world.

- Go beyond federal issues. While a lot of noise around politics and government comes from the federal level, Green said it’s important that students study state and local issues. Students in the Mikva Challenge have been interested in everything, from a lack of dog parks to street light issues. In those more local spaces are where folks can find commonalities, she said.

- Remember there’s a spectrum of experiences when it comes to civics – and remember to talk to students, Gallivan said. Different students come with different experiences to share. That means reporters should seek out students from a diversity of backgrounds, he said.